Memory

Who is the keeper of our identities?

Dear Friend,

Buckle up. Another long one.

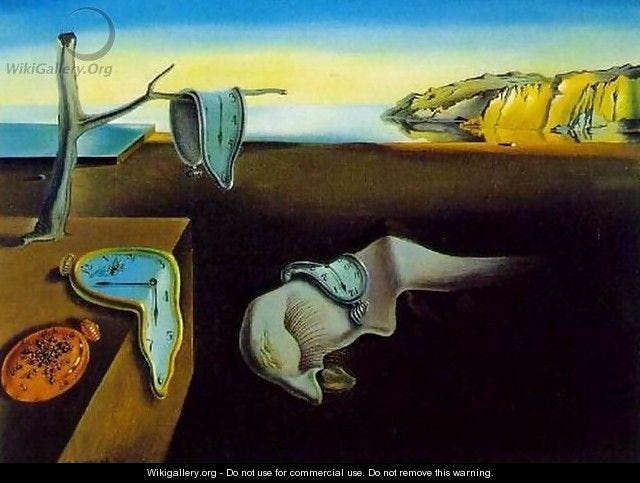

Do you happen to recall the first time you saw Dali’s “The Persistence of Memory?”

I do. It wasn't the real thing, of course, but most likely a poster an upperclassman (whose first name, Lance, I somehow remember after forty years) had brought in for a presentation he was giving in art class, or maybe even Bible class. Maybe I ran into him in the hall. Maybe it was the cafeteria. Who can say?

It was fall. I was a sophomore and I had just transferred to a new private Christian school that largely erased the line between my church friends and my school friends. It seemed that most everyone from Sunday School was also suddenly at my school on Monday morning. My church friends were kind, but they had been spending six of seven days together each week since elementary school. They spoke a different language, and they were all fluent. I was not fluent. I was the kid who showed up on Sundays. I was well treated. Like an acquaintance you meet occasionally at a party. Nice to chat with, but the conversation rarely went past the weather and football, which is what we learned to talk about in southern Ohio in the fall.

My old school friends were put on hold until summer.

That is the context of my having seen, for the first time, Dali’s classic painting. I was in a place I did not recognize, and I felt myself unrecognizable. I remember feeling a thrill and an immediate connection to Dali. I thought of Dali as a kid who probably showed up on Sundays, but whose name people didn’t always remember. I imagined Dali as a guy who recognized that things were not always what they seemed, and I was deeply drawn to both what he saw and what he painted.

That is not to say I recognized anything he painted, or that “I got it.” I did not get it. It was disorienting and strange, but I was drawn to the disorientation and strangeness, as he must have been, and I think I felt a little less alone. Even then, I recall, I did not want to live in a world so small it could fit neatly into my head, although I doubt I would have said it that way at fifteen. I remember feeling glad that Salvador Dali was still alive and had dared to paint this strange and beautiful thing and that there was a place in the world for it. I remember a similar feeling when a friend introduced me to Kandinsky decades later.

Maybe you had a Salvador Dali. Perhaps her name was Emily Dickinson. Or Gene Stratton Porter. Or Dale Chihuly. Maybe it was Einstein or Oppenheimer or Vincent van Gogh or Eddie van Halen or Bruce Springsteen. I hope you had someone who suggested there is a grandness and gladness in the world that we only get hints to. I hope you remember her name.

It’s hard for me to know how much of what I am writing is capital-T true, how much is highly suspect revisionist self-analysis, and how much is just pure fantasy. That’s the nature of memory, isn’t it?

I have been wondering a lot about memory, and wondering especially about its persistence, after all. Wondering about where we house our memories. And mostly wondering about the relationship between memory and identity.

Kathryn and I spent last weekend in the Allegheny mountains. Each morning she and I would sit on the porch overlooking a valley whose name I don’t know, and whose magnificence defies description. We sipped coffee, ate sliced fruit, admired the view, and read David Whyte’s Consolations together.

There is a lovely essay in the book on memory in which Whyte seems to question the unquestionable orthodoxy of our culture that the now is sovereign. Whyte rises above convention to admire the dance of past and present and future from the great vista of memory. He writes:

“Memory is an invitation to the source of our life, to a fuller participation in the now, to a future about to happen, but ultimately to a frontier identity that holds them all at once. Memory makes the now fully inhabitable…

…A full inhabitation of memory makes human beings conscious, a living connection between what has been, what is, and what is about to be.”

This rings true and beautiful. And then Whyte undoes me in the very next line:

“Robbed of our memory by Alzheimer’s or by a stroke, we lose our identities. Memory is the living link to personal freedom.”

These sentences stung. I find myself wondering what it means to “lose our identities?” It seems one of those phrases that we use without really knowing what we mean, and that bothers me. More than that, Whyte seems to suggest that we are the exclusive guardians of who we are, and that if we fall down on the job? Well, then we are done. And the means by which guard ourselves is memory, a shield that resides in our brains, but can be taken from us by ordinary life. Naturally, I want to reject this with all my might, and not simply because of brain cancer (although, let’s be honest, that is part of it). But also because I cannot accept the idea of our identity, whatever that means, hanging by a thread to an imperfect and stunningly fallible brain. A brain that shakes up memories like Yahtzee dice, and throws them on the table differently each roll.

Does our identity change with each roll - each time a memory morphs? Some might take comfort in this thought. I do not. Strangely, it’s less important for me to know who I am than it is to know that I am. But if they each depend on memory, neither is assured.

I’m not sure even Descartes took it that far in the cogito. The proof of our existence is found only in our thinking, Descartes seemed to suggest. Our remembering feels like a higher bar to me, and one I’m glad not to have to clear in order to be.

If I haven’t mentioned it, I commend Buechner’s Crazy, Holy, Grace to you. Buechner writes about memory, too. There is a particular essay called “A Room Called Remember” in which he recounts a dream in which he discovers a room where he “felt happy and at peace, where everything seemed to be the way it should be and everything about myself seemed the way it should be too.”

The essay explores, among other things, the distance between memories that “come and go more or less on their own and apart from any choice of ours” and memories that we seek out and retrieve. The gap between memories of chance and memories of volition. The room called remember, writes Buechner, “is a room we can enter whenever we like so that the power of remembering becomes our own power…a room where all emotions are caught up in and transcended by an extraordinary sense of well-being.”

To me, there is a deep connection between what Buechner is suggesting and what Whyte describes as identity. I think I hear Buechner suggesting that our intentional memory is a link to identity and contentment, and we the have ability to click on that link whenever we like. And that it is our gift to be able to choose when and how and where we return to the “Room Called Remember.” And that to be fully human is to retain this gift of choice.

It’s a lovely thought, but does it ring true to you? I want it to be true. So badly. I want to have those touchstone memories to which I can return at any time. Memories that reset the balance of the world whenever I choose. And while I have some such memories, I rarely remember even to look for them when the world tilts on itself.

In some ways, this point of view seems so ubiquitous that it makes little sense even to question it. How many ads will you see this week promising to help you sharpen and preserve your memory? How many times will someone suggest that a robust memory and the ability to manage it make for good life? But is that really so, and can we even preserve memory by our own effort?

And of course, this effort and striving to remember, if it exists exclusively in the brain, will ultimately fail. It does. It must.

This is very much a thought in progress, but the idea that it’s on me to manage my memory leads immediately and directly to despair. It must, I think, because the task is hopeless. Isn’t it?

So then what?

It seems to me that remembering must either mean more than “holding something securely in my brain.”

Or perhaps, managing my memory, even trying really, really hard to remember, isn’t my work at all.

Most of this week, I leaned to the former. Thinking up ways I might plant memories ever deeper, where they might rest like cicadas until it is their time. Doing things that would invite memory deep into the my pores of my heart…into my actual being. I imagined a time when my cognitive abilities will inevitably decline, but if I do this right, even then I might walk through the woods and hear the birdsong or see a spider web and know in some deep part of me, far deeper than my head, who I am and that God is with me and that I am loved….even if I had no specific memory to point to that would lead me that conclusion. That it is my job to lean into God’s love while I can consciously choose to do so, so that when I cannot make that choice, I will still have the embodied memories of God’s goodness and sovereignty and here-ness and with-ness to sustain me.

A friend once suggested that the Israelites often seemed to find themselves in trouble for failing to remember the Sabbath, a curious choice of words for one of the Ten Commandments. I suppose there are a number of ways to interpret this, but I deeply appreciate Abraham Heschel’s suggestion that Sabbath exist, in part, to remind us of our relationship with the divine - to remind us that “we are not merely beasts of burden.” The Sabbath, suggests Heschel, is

“… a mine where spirit’s precious metal can be found (remembered) with which to construct the palace in time…in which the human is at home with the divine.”

Perhaps Sabbath is our weekly invitation to remember the one in whom our identity is found. To remember whom to praise. Once again, it’s about remembering. And that Sabbath is one way to plant these seeds in the very deepest part of our beings.

But I’m not sure even of this.

Let me be clear, I am not rejecting this approach…except I am rejecting that it is my job to focus on an outcome. Remembering Sabbath is good. Walks with God are good. But it’s about the walk. Not about any benefit I might receive beyond walking. These are not my seeds to plant, to water, or to nurture.

As the week has moved on, I’ve instead come to consider that this is yet another surrender moment. That I no more need to manage this than I need to manage gravity, which I am not so good at, it seems.

David writes in the Psalms:

“You keep track of all my sorrows. You have collected all my tears in your bottle. You have recorded each one in your book."

I hear this as:

I’ve got you, dear child. I will keep track of your sorrows, but not only your sorrows. Also your joys, your laughter, and every sunrise that brought you to your knees. Every poem that cracked your heart wide open. The painting in the Chrysler that you can't remember already? I remember. Every swim meet and every wet hug at the end of every race. The time you noticed me at the Springsteen concert? Yep. Every kiss. Every touch. Every mosquito bite. I remember all of it. I am in you and you in me, and I will remember you when you do not remember you.

At Calvary, one of the men crucified with Jesus said:

"Jesus, remember me when you come into your kingdom power.” He did not say, “How will I remember?” He simply asked that Jesus remember him.

And Jesus replied simply, “Truly I say to you, today you will be with me in Paradise.”

There is a part of me that embraces this as the very definition of “the persistence of memory.” That God remembers me. That this life is not a great scavenger hunt and it is not my duty to collect and retain the right memories to piece together my identity.

No.

My identity is already secure, whether or not I am able to recognize that. I need only to walk near to God.

Oremus,

Chris

Buechner’s words definitely ring true for me. However, I struggle sometimes with memories of difficult moments in life surfacing, always uninvited. These are the memories I wish I WOULD lose since dwelling on them serves no purpose. Embracing Buechner’s practice could be a way to divert negative thoughts.

Whyte seems to have not thought all of this through nearly as well as you have. But that does not surprise me :)

Wonderful thoughts Chris. Thank you!

Oh, what a resonance this is for me, Chris. The prospect of my imminent memory scratches at my mind like the next day’s mosquito bite. Thank you for helping the mystery find its footing.

Warm breeze on my face with sunshine penetrating my eyelids…

Musical artists of the 70’s crackling through the humidity assaulted Pioneer at the community pool…

Mourning doves lending their tranquil news to the chipper montage of the morning proclamations…

The wild abandon of running down a generous slope faster than any human could surely have ever done…

Burning leaves (is that still legal?)… Norman Rockwell paintings… the earthy, woodsy smell of a baseball glove… self-picked wild berries…

Will the cicadas hold them safely?

Can others’ memories become my own? Because, as you mentioned, mine may not actually hold a capital T anyhow. Or maybe, just maybe… they’re only ours until they’re not. And maybe length of memory means less and less. What we have at the time is what we hold. I will work on letting God be my memory keeper (He’s probably much more reliable than the cicadas anyhow).

Once again… thank you for broadening my mind and my heart, Chris!